In this interview, Maria Corredor – a PhD student from Cornell University – shares her passion for cursive handwriting and the importance of making historical manuscripts accessible to a wider audience through the Atlantic Seascapes Project. For Maria, the leader of the project, cursive handwriting, and old manuscripts are not just relics of the past, but vital connections to the stories of pirates, corsairs, explorers, and ordinary people who shaped the history of the Atlantic. These elements are essential in preserving and understanding the rich and complex history of the Caribbean and the Atlantic world, offering invaluable insights into the lives and experiences of those who lived centuries ago.

The Atlantic Seascapes Project

Question (Q): Maria, could you tell us about the inspiration behind the Atlantic Seascapes Project?

Maria Corredor (MC): The Atlantic Seascapes Project was born out of a deep concern for preserving and studying our shared past, especially the experiences of the Caribbean and the broader Atlantic world. The Atlantic has always been a space of encounters—where indigenous people, maroons, pirates, corsairs, sailors, fishermen, and enslaved individuals crossed paths. This shared history shaped the relationships within the Americas and between the Americas and Europe, Asia, and Africa.

During the independence movements in Latin America, people of the sea played a pivotal role in this Atlantic history. Despite the importance of the Caribbean, many of the documents needed to reconstruct these experiences are difficult to access today. This project aims to make those documents available to the public. We started with documents from the Secretariat of the Navy of Colombia (Secretaría de Marina), dating between 1816 and 1830, which also cover present-day Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, and Ecuador. These documents are housed in the National Archives of Colombia (Archivo General de la Nación), but they were not previously digitized, and the printed catalog descriptions were not always helpful for research.

Reading Cursive Handwriting

Q: What role does cursive handwriting play in your work with these historical documents?

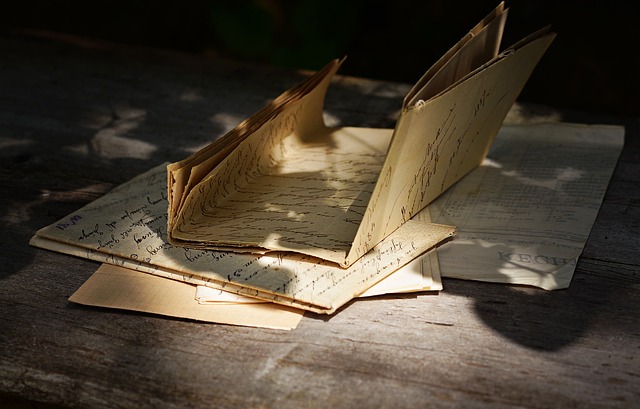

MC: Learning cursive has opened windows to the past for me. By knowing how to read cursive handwriting, I’ve been able to approach historical documents of pirates and corsairs, explorers, and sailors from two, three, and even four hundred years ago. Cursive handwriting is like a key; it allows you to unlock stories that have been hidden in the folds of history. These are stories written by people who lived through significant events, and their experiences are captured in the strokes of cursive script.

For instance, the Atlantic Seascapes Project involves a great deal of archival work, much of which includes reading and transcribing cursive documents. These documents are not only valuable for their content but also for the way they connect us to the past. The act of reading cursive handwriting forces us to slow down and engage more deeply with the text and with the inhabitants of the past.

Physical and Digital Manuscripts

Q: The project’s website features a collection of these old manuscripts. How do you see the relationship between the physical manuscripts and their digital counterparts?

MC: The physical manuscripts are, of course, irreplaceable treasures. They carry with them the weight of history, the texture of the paper, and the faint smell of the past. However, these documents are often fragile, and accessing them can be challenging, especially for those not located near the archives. That’s where the digital versions come in. By digitizing these documents and making them available on our website, we’re preserving them for future generations while also democratizing access to this crucial historical information.

The digital manuscripts on the Atlantic Seascapes Project website are part of a broader effort to make history more accessible. For many researchers, students, and history enthusiasts, visiting an archive in person is not always feasible. The website allows them to explore these documents from anywhere in the world. It also provides tools for searching and analyzing the content, which can be incredibly helpful for academic research. But beyond the academic value, there’s something profoundly personal about being able to read a letter written by a sailor hundreds of years ago, in the same handwriting they used: It’s a direct connection to the past.

The Challenges

Q: What have been your main challenges in this project?

MC: One challenge is the sheer volume of documents. The Atlantic Seascapes Project started with a focus on documents from the Secretariat of the Navy of Colombia, but the potential scope is much broader. We’re constantly discovering new materials that could be added to the collection, which means that the project is ongoing.

We’ve also had to navigate the technical challenges of creating a user-friendly website. We wanted to make sure that the digital manuscripts were not only accessible but also easy to navigate and search. Thanks to the support of the Caribbean Digital Scholarship Collective and Cornell Library Digital Humanities, we’ve been able to develop a platform that meets these needs. The website uses a format called CollectionBuilder-CSV, which allows us to organize and present the documents in a way that’s both visually appealing and functional.

Preserving handwritten history

Q: How do you hope the Atlantic Seascapes Project will impact the study of history, particularly in the Caribbean and Latin America?

MC: I hope that the Atlantic Seascapes Project will serve as a valuable resource for students, researchers, and anyone interested in the history of the Caribbean and the Atlantic world. By making these documents accessible, we’re not only preserving history but also opening up new avenues for research and discovery. I believe that history should be a conversation, not just between scholars but between the past and the present. By learning to read cursive handwriting and engaging with these old manuscripts, we’re participating in that conversation.

In particular, I hope that the project will be useful for those in Colombia, Venezuela, and Panama who are looking to understand their history. But also, as the Atlantic is a space of encounters, we expect that a broader audience will be interested in themes like migration, diaspora and connections. After all, the sea is a place of encounter and history. By exploring the stories captured in these documents, we can gain a deeper understanding of how the past has influenced the present and how it continues to shape the future.

Cursive and Manuscripts

Q: Finally, what advice would you give to someone who is just beginning to explore historical manuscripts or learning cursive handwriting?

MC: Patience and curiosity are key. Learning cursive handwriting can be challenging at first, especially if you’re not used to it. But it’s worth the effort. Once you start to recognize the shapes of the letters and the flow of the handwriting, it becomes like a second language. And with that language, you gain access to a whole new world of stories and knowledge. I highly encourage you to use the Cursive Generator!

When it comes to exploring historical manuscripts, I would say don’t be intimidated. Start with something simple, maybe a letter or a journal entry. Take your time to look at the handwriting, the way the letters are formed, and the nuances in the script. Practice yourself by copying single letters and words to get the ability to identify characters faster. You can also look up different types of handwriting. Sometimes medieval scripts, with the big rounded letters of the gothic, could give us a clue on how to start this process of fascination with cursive.

Maria Corredor

Maria is a Colombian historian and archivist currently pursuing a Ph.D. in history at Cornell University. Her research focuses on the colonial history of Latin America and the Caribbean, with a strong interdisciplinary approach that incorporates anthropology and geography. Maria’s passion for history extends beyond traditional academic boundaries, as she is dedicated to making historical documents accessible to a broader audience. Through the Atlantic Seascapes Project, she explores the Atlantic as a space of encounters and aims to provide valuable resources for students and researchers, particularly in Colombia, Venezuela, and Panama.